Astro Session: July 9, 2018

I recently bought the William Optics FLAT 6A II, and finally made it out under the stars to take some sub-exposures. I paired it with my GT-81 and ZWO ASI071MC color CMOS camera. The FLAT 6A II is a 0.8x reducer/field flattener; it's adjustable for different focal lengths, and so far, with my limited use, it appears to be quite a leap over the old William Optics F6-A I've used for a few years. The ASI071 has an APS-C sized sensor, and anyone with a large sensor astro camera or DSLR knows if you don't want field curvature with your refractor you need some sort of flattener. The FLAT6AII design makes it easy to dial in the correct distance for the scope you're using. The old reducer/flattener worked, but I had to test out a dozen different flattener to sensor distances, and still had to do some cropping and processing to fix the corners. This new FLAT 6AII provides a fairly flat field across the entire view. Equipment: William Optics GT-81 + FLAT 6A II 0.8x reducer f/4.7, ZWO ASI071MC-Cool color CMOS camera - gain 0 offset 8, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam + 130mm guide scope.

I recently bought the William Optics FLAT 6A II, and finally made it out under the stars to take some sub-exposures. I paired it with my GT-81 and ZWO ASI071MC color CMOS camera. The FLAT 6A II is a 0.8x reducer/field flattener; it's adjustable for different focal lengths, and so far, with my limited use, it appears to be quite a leap over the old William Optics F6-A I've used for a few years. The ASI071 has an APS-C sized sensor, and anyone with a large sensor astro camera or DSLR knows if you don't want field curvature with your refractor you need some sort of flattener. The FLAT6AII design makes it easy to dial in the correct distance for the scope you're using. The old reducer/flattener worked, but I had to test out a dozen different flattener to sensor distances, and still had to do some cropping and processing to fix the corners. This new FLAT 6AII provides a fairly flat field across the entire view. Equipment: William Optics GT-81 + FLAT 6A II 0.8x reducer f/4.7, ZWO ASI071MC-Cool color CMOS camera - gain 0 offset 8, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam + 130mm guide scope.

Testing:

Testing:

With the GT81 and ASI071 I get a 3.54° x 2.35° field of view, and I can capture some big chunks of the night sky. Here are three from the last two nights: [1] the Pelican Nebula (IC 5070) and the edge of the North America Nebula (NGC7000) at the bottom, [2] IC 1396 nebula with the Elephant's Trunk at the top and the Garnet Star bottom left, and [3] M31, our galactic neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy.

Pelican Nebula image info: ZWOASI071MC 39 x 240 second color subs stacked in DSS, processed in PSCC2018

IC 1396 region image info: ZWOASI071MC 21 x 300 second color subs stacked in DSS, processed in PSCC2018

The Andromeda Galaxy. The last time I photographed Andromeda (M31) was 2015, maybe fall of 2014? It's been a while. I was using a DSLR--that was the only camera I had, and I had it on a terribly-used Celestron CG-5 equatorial mount with some aftermarket RA/DEC motors. By "terribly-used" I mean you could drive a truck through the gear backlash. Even so, I still managed to get some decent 30-second exposures of Andromeda, Orion Nebula, and other big bright targets in the sky. Well, I'm back with our galactic neighbor, and with much better gear: 192 x 120-second sub-exposures stacked in DSS, processed in PSCC2018, ZWO ASI071MC camera at -10C, William Optics GT81 APO, iOptron CEM25P EQ mount.

Posted July 9, 2018

Astro Session: July 7, 2018

Our galactic neighborhood, looking toward the center, with 13 stacked 15 second exposures, Nikon D750, Rokinon 10mm f/2.8 lens. What's crazy is this is with a decent DSLR camera, lens, a tripod, and some free image stacking software (DSS). I did the stretching in Photoshop CC--"stretching" is when you adjust contrast, intensity values, to bring out the features of whatever you're shooting--in this case the north end of the Milky Way Galaxy, our home. Let me point out some interesting features: starting at the left, that vivid red star is the "Garnet Star" (Mu Cephei), and that's right next to some cool nebulosity that includes the Elephant's Trunk Nebula (IC 1396), a little ways along, you see that blocky reddish region? That's the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) with the star Deneb (19th brightest star in the night sky). Deneb forms the northernmost (leftmost in this shot) point of the famous "Summer Triangle". The other two points are Vega, the 5th brightest star in the night sky (to the right and above the Milky Way core in this shot), and Altair (12th brightest) a little more to the right and below the Milky Way core. Moving along the galaxy to that bright region on the bottom side of the core, about halfway between Altair and the powerlines--if you really zoom in, you'll see the Wild Duck Cluster (M11). Now look just left of where the powerlines cross, those grayish-pink cloudy areas? That's where you will find the Eagle Nebula (Messier 16, NGC 6611) and the Swan Nebula (M17). That bright point of light in the middle of the powerlines is the planet Saturn, which is moving along the ecliptic and right now it's in a pretty good place for viewing. Just right of that are a few more cloudy areas. That's where you would look for the Lagoon Nebula (M8, NGC 6523) and Trifid Nebula (M20, NGC 6514). Somewhere along the Milky Way--this is where you will mostly likely find me focusing my telescope all the through the summer and fall. I almost see this shot as a map of places to visit from afar, and the cool thing is you really don't need to setup the astro gear for this. You can create your own galaxy map, as long as your camera can handle long exposures (not that long, only 15 seconds) and you have it on a tripod with a remote shutter control. And this is only part of the sky from where I'm standing on our little planet! Another way to put this image in perspective is here in the northern hemisphere, around 43° latitude, I don't have enough of a view south (blocked by hills and trees) to see Sagittarius A*, which marks the center of our galaxy, and this far north there's a sky full of other galaxies, a large section of our own galaxy, nebulae, and other deep space objects that I can't ever see from here--that I would have to travel below the equator to see. Some day!

Posted July 7, 2018

Astro Session: July 3, 2018

The Dumbbell Nebula (M27, NGC 6853), also called the Apple Core, is a planetary nebula in the constellation Vulpecula. I setup the AstroTech with 1350mm focal length, paired with the Atik 414EX mono CCD. This gives me .98" / pixel resolution and oversampling, but still managed to get some detail out of the nebula. (Imaging info: 63 x 90 second subs in OIII, 96 x 60 sec. subs of Ha. + 20 dark frames stacked in Nebulosity, processing in PSCC2018. Equipment: AstroTech AT6RC f/9 Ritchey-Chrétien, Atik 414EX mono CCD, 7nm Optolong 2" Ha filter, 8.5nm Baader 2" OIII filter, Orion Atlas EQ-G Mount, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam + WO 50/200mm guide scope)

The Dumbbell Nebula (M27, NGC 6853), also called the Apple Core, is a planetary nebula in the constellation Vulpecula. I setup the AstroTech with 1350mm focal length, paired with the Atik 414EX mono CCD. This gives me .98" / pixel resolution and oversampling, but still managed to get some detail out of the nebula. (Imaging info: 63 x 90 second subs in OIII, 96 x 60 sec. subs of Ha. + 20 dark frames stacked in Nebulosity, processing in PSCC2018. Equipment: AstroTech AT6RC f/9 Ritchey-Chrétien, Atik 414EX mono CCD, 7nm Optolong 2" Ha filter, 8.5nm Baader 2" OIII filter, Orion Atlas EQ-G Mount, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam + WO 50/200mm guide scope)

Posted July 3, 2018

Astro Session: June 30, 2018

The Eagle Nebula (Messier 16, NGC 6611, Star Queen Nebula) is an open star cluster and emission nebula in the constellation Serpens, about 7000 lightyears away from us. Imaging Info: 96 x 240 sec. Ha + 42 x 240 sec. OIII frames stacked in DSS, processed in PSCC2018. These frames were taken over several nights. You can see the numbers are a bit unbalanced, but the clouds moved in during the OIII sequence last night, and there was nothing I could do. I went ahead and stacked and processed them as they are. I'll probably come back to this one in the future with more oxygen-3 (and maybe sulphur-2) to achieve something like the actual proportional levels of light from the nebula across these bandpasses. Equipment: William Optics ZS61, Atik 414EX mono CCD, 12nm Astronomik Ha filter, 12nm Astronomik OIII filter, CEM25P EQ Mount, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam + Orion TOAG, INDI/KStars/Ekos control software. Location: Stratham, New Hampshire, Bortle: 4, SQM: 20.62 https://www.astrobin.com/353803

Posted June 30, 2018

Astro Session: June 22, 2018

The view from my backyard, with the right equipment focused on a particular part of the sky: Cygnus Wall region of NGC 7000, the North America nebula, imaged in narrowband Ha and OIII. The way narrowband imaging works is by filtering out all light except for an allowed narrow bandpass at specific locations in the electromagnetic spectrum. A hydrogen-alpha (Ha) filter will only allow light to pass through to the camera sensor around 656 nanometers, which is out at the red end of the spectrum, and an oxygen-3 (OIII) filter will only allow light to pass through around 501nm, which is in the middle of the blue and green ranges. When I say red, green, blue, I'm talking about where these bandpass lines fall within the scope of the visible spectrum, which starts around 390 and goes to 700 or so (for humans). I shot the oxygen-3 sub-exposures last week, and the hydrogen-alpha subs last night. When you process these separately filtered images into one color image, you may get the Ha coming out vivid red to rust red, and the OIII coming out in blues and greens. The Cygnus Wall is that bright, rolling line across the middle where you have a lot of concentrated star formation, but this area of NGC 7000 also has lot of dust and debris drifting in front of it--the dark reddish-brown regions across the top and right side. (Imaging info: 42 x 300 second subs in OIII, 40 x 300 sec. subs of Ha. + 20 dark frames stacked in DSS, processing in PSCC2018 + Astronomy Tools actions & Annie's Astro actions. Equipment: William Optics ZS61, Atik 414EX mono CCD, 7nm Optolong 2" Ha filter, 8.5nm Baader 2" OIII filter, CEM25P EQ Mount, ZWO ASI120MM-S Guide Cam, https://www.astrobin.com/352528).

Posted June 22, 2018

Astro Session: June 16, 2018

It was narrowband time last night in the backyard. I took a couple hours of hydrogen-alpha (Ha) sub-exposures of M17, the Swan Nebula in the constellation Sagittarius. M17 is about 5,500 light-years away. It's also called the Omega Nebula, Checkmark Nebula, and sometimes the Horseshoe Nebula, but all I see is a swan--with a black beak, neck arched forward, and wings outstretched. The bright region in the middle is the swan's chest. I started to take a few OIII frames on the 16th, but by that time M17 was heading back toward the southern horizon, and so I jumped over to the "Cygnus Wall" in NGC 7000 (North America Nebula). I captured several hours of OIII data there, amazing stuff, and I've already posted the finished image in Ha and OIII. I came back to M17 on the 21st, and took another 40 x 300 second subs in OIII. (M17 info: Ha 16 x 300 second + 82 x 120 second exposures + 20 dark frames, OIII 40 x 300 second exposures + 20 dark frames, stacked in DSS, William Optics ZS61, Atik 414EX mono CCD, 7nm Optolong 2" Ha filter, 8.5nm Baader 2" OIII filter, CEM25P EQ Mount, QHY5III178 guide cam with the Orion TOAG, https://www.astrobin.com/352947).

UPDATE: The Swan Nebula (M17) bi-color narrowband with the WilliamOptics ZS61 and the Atik 414EX. I shot the hydrogen-alpha frames on June 16th (16 x 300 second exposures + 82 x 120 second exposures) and I came back on the 21st to shoot 40 x 300 second exposures in oxygen-3. I decided not to shoot sulphur-2 frames based on the wonderful result with bi-color for my Cygnus Wall image set (6.8 hours of Ha + OIII). For the Swan Nebula (this post) and Cygnus Wall (last post) images I used the Hydrogen-alpha/Oxygen-3 bi-color process developed in an article by Travis Rector, et. al. in The Astronomical Journal here: https://doi.org/10.1086/510117, and detailed here: https://www.starrywonders.com/bicolortechniquenew.html

Posted June 16, 2018

Astro Session: June 8, 2018

How about a little Voldemort with your Astronomy? Here's Barnard 104, the Fish Hook Nebula (backward checkmark nebula was already taken?), just left of the star beta Scuti in the constellation Scutum--along with several other absorption nebulae in the Barnard Catalogue, 113, 111, 110, 107, and B106. (See the image below). These are the dark cloudy regions across the middle, which stand out against the glow of a billion stars in this area of the Milky Way Galaxy. (Okay, I'm being a bit deceptive with the drama there. It's probably more like 5 or 10 billion). Oh, and let's not forget NGC 6704, the open star cluster toward the bottom in the center. A note on the "Barnard Catalogue", which is what I've always called it: I just found out the official name for it is the very Harry Potter sounding, Barnard Catalogue of Dark Markings in the Sky. Go home, Death Eaters! The star gazing geeks got here first! (ZWO ASI071MC cooled CMOS camera at -10°C, iOptron CEM25P EQ mount, William Optics ZenithStar 61 f/5.9, 12 x 120 sec. sub exposures, stacked in DSS. Location: Stratham, New Hampshire, US. Bortle 4).

How about a little Voldemort with your Astronomy? Here's Barnard 104, the Fish Hook Nebula (backward checkmark nebula was already taken?), just left of the star beta Scuti in the constellation Scutum--along with several other absorption nebulae in the Barnard Catalogue, 113, 111, 110, 107, and B106. (See the image below). These are the dark cloudy regions across the middle, which stand out against the glow of a billion stars in this area of the Milky Way Galaxy. (Okay, I'm being a bit deceptive with the drama there. It's probably more like 5 or 10 billion). Oh, and let's not forget NGC 6704, the open star cluster toward the bottom in the center. A note on the "Barnard Catalogue", which is what I've always called it: I just found out the official name for it is the very Harry Potter sounding, Barnard Catalogue of Dark Markings in the Sky. Go home, Death Eaters! The star gazing geeks got here first! (ZWO ASI071MC cooled CMOS camera at -10°C, iOptron CEM25P EQ mount, William Optics ZenithStar 61 f/5.9, 12 x 120 sec. sub exposures, stacked in DSS. Location: Stratham, New Hampshire, US. Bortle 4).

So, all in all, a successful night of astronomy stuff, even with the clouds rolling in around 2 am. Here are a couple more wide-field shots from the session, the Eagle Nebula and the Sadr Region--the diffuse nebula (IC 1318) around gamma Cygni, also called Sadr (center star in the constellation Cygnus).

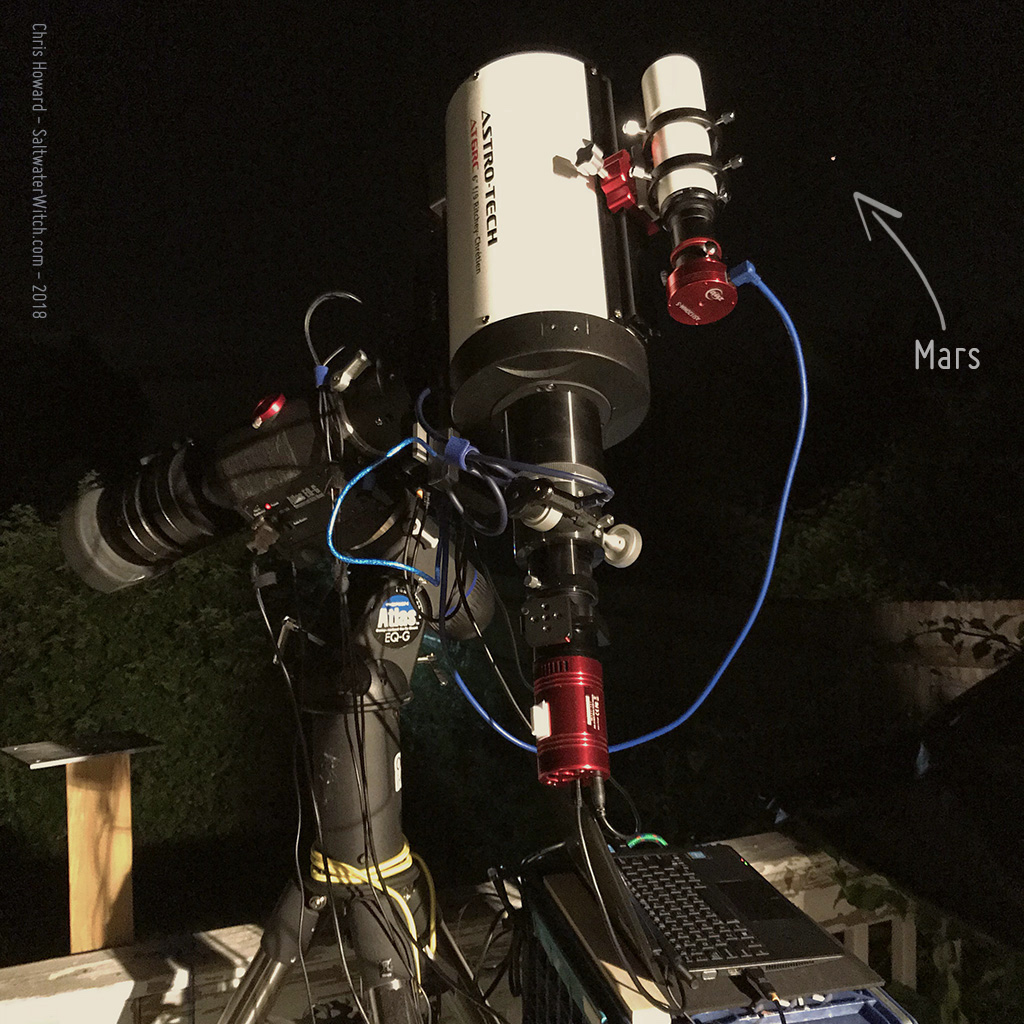

I spent a few hours last night dialing in the Orion "TOAG" or Thin Off-Axis Guider, which I bought a couple years ago, but have never been able to get working properly. I've tried seven or eight times, added it to my imaging train a couple times a year, attempting to get things working without success. Well, I went at it again last night, and you know what? It came together. I still have some weirdness to tinker with--to work out, but for the first time I wasn't guiding with a separate scope. I was guiding at the same focal length as the ZS61 using a pick-off prism that directs a portion of the field of view up into the guide camera. Here's the setup I used last night to dial-in the distance between the primary camera and guide camera, and then bring everything into focus. I ended up with some pretty cool shots, but my main purpose was to get Off-Axis Guiding (OAG) adjusted and working--and that was with me slewing around the sky to clear areas between banks of clouds to find some halfway interesting targets. In this setup I'm using my trusty ZWO ASI120MM-S for guiding, and the ZWO ASI071MC cooled color camera for the primary. The goal here is to be able to guide (track the motion of the earth against the star field to a very fine degree, and make small incremental adjustments to the EQ mount) so that I can take long exposures without worrying about the external guidescope issues I know all of you care deeply about, like field rotation and differential motion between a guide scope and imaging telescope. I have been able to take 20 minute exposures with a guidescope and camera, but the stars are not as sharp as I would like--think pressing down the button of your camera and holding the shutter open for 20 or 30 minutes and have everything in the field of view remain in sharp focus. That's essentially what the guiding system accomplishes, taking continuous images of the stars and feeding them to some pretty sophisticated software that controls the motion of the equatorial mount (that's the white z-shaped device with the black boxes on which the telescope is fastened and balanced).

I spent a few hours last night dialing in the Orion "TOAG" or Thin Off-Axis Guider, which I bought a couple years ago, but have never been able to get working properly. I've tried seven or eight times, added it to my imaging train a couple times a year, attempting to get things working without success. Well, I went at it again last night, and you know what? It came together. I still have some weirdness to tinker with--to work out, but for the first time I wasn't guiding with a separate scope. I was guiding at the same focal length as the ZS61 using a pick-off prism that directs a portion of the field of view up into the guide camera. Here's the setup I used last night to dial-in the distance between the primary camera and guide camera, and then bring everything into focus. I ended up with some pretty cool shots, but my main purpose was to get Off-Axis Guiding (OAG) adjusted and working--and that was with me slewing around the sky to clear areas between banks of clouds to find some halfway interesting targets. In this setup I'm using my trusty ZWO ASI120MM-S for guiding, and the ZWO ASI071MC cooled color camera for the primary. The goal here is to be able to guide (track the motion of the earth against the star field to a very fine degree, and make small incremental adjustments to the EQ mount) so that I can take long exposures without worrying about the external guidescope issues I know all of you care deeply about, like field rotation and differential motion between a guide scope and imaging telescope. I have been able to take 20 minute exposures with a guidescope and camera, but the stars are not as sharp as I would like--think pressing down the button of your camera and holding the shutter open for 20 or 30 minutes and have everything in the field of view remain in sharp focus. That's essentially what the guiding system accomplishes, taking continuous images of the stars and feeding them to some pretty sophisticated software that controls the motion of the equatorial mount (that's the white z-shaped device with the black boxes on which the telescope is fastened and balanced).

Posted June 8, 2018

Astro Session: June 2, 2018

The Crescent Nebula (NGC 6888) with two channels, hydrogen-alpha and oxygen-three. 4 x 1200 second exposures for the Ha (mostly red channel), and 10 x 600 second exp. for the OIII (mostly blue channel). I didn't get nearly enough of the blue halo around the Crescent as I would have liked. I'll probably need to go to 20-minute exposures in OIII next time--or more 10 minute ones.

The Crescent Nebula (NGC 6888) with two channels, hydrogen-alpha and oxygen-three. 4 x 1200 second exposures for the Ha (mostly red channel), and 10 x 600 second exp. for the OIII (mostly blue channel). I didn't get nearly enough of the blue halo around the Crescent as I would have liked. I'll probably need to go to 20-minute exposures in OIII next time--or more 10 minute ones.