Custom power cable for the Sky-Watcher

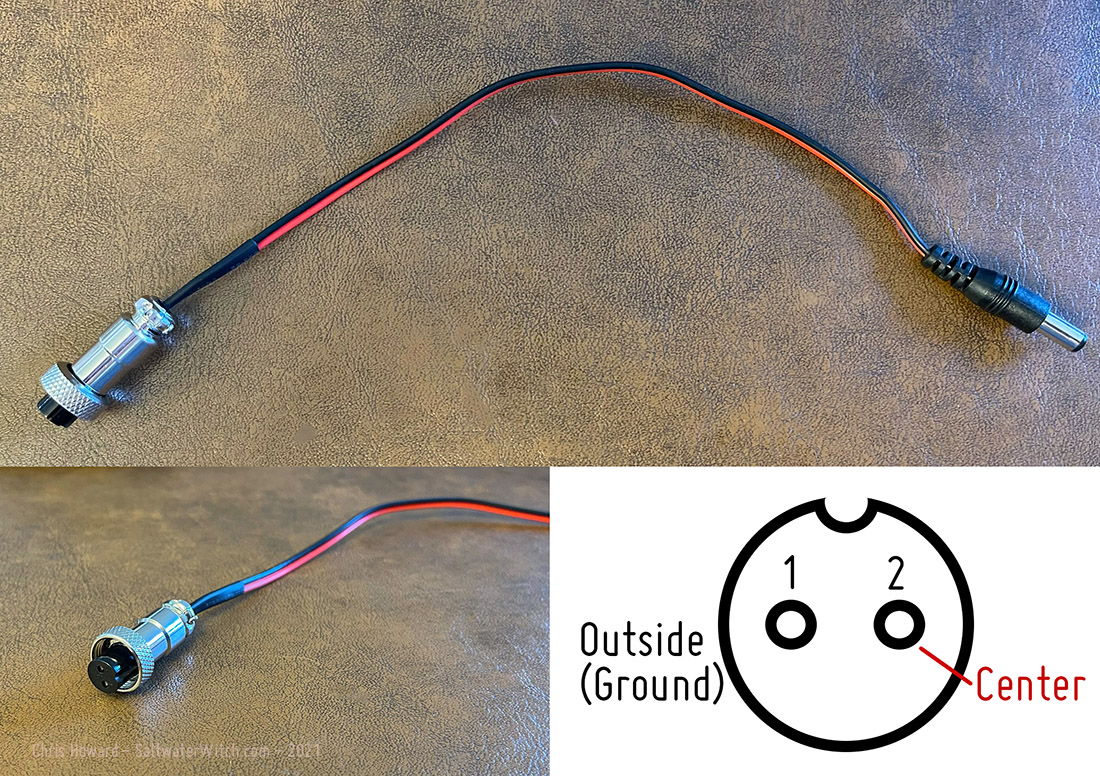

Scrounged up a couple parts I bought a while back for this specific project, but just getting around to it now. The Sky-Watcher EQ6-R Pro telescope mount uses a 2 pin GX12-2 aviator plug for 12vdc power. I bought a couple off Amazon earlier this year, and today I soldered up the 5.5mm x 2.1mm power jack after testing which pin is ground and which has voltage. (https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07DC7KP8H).

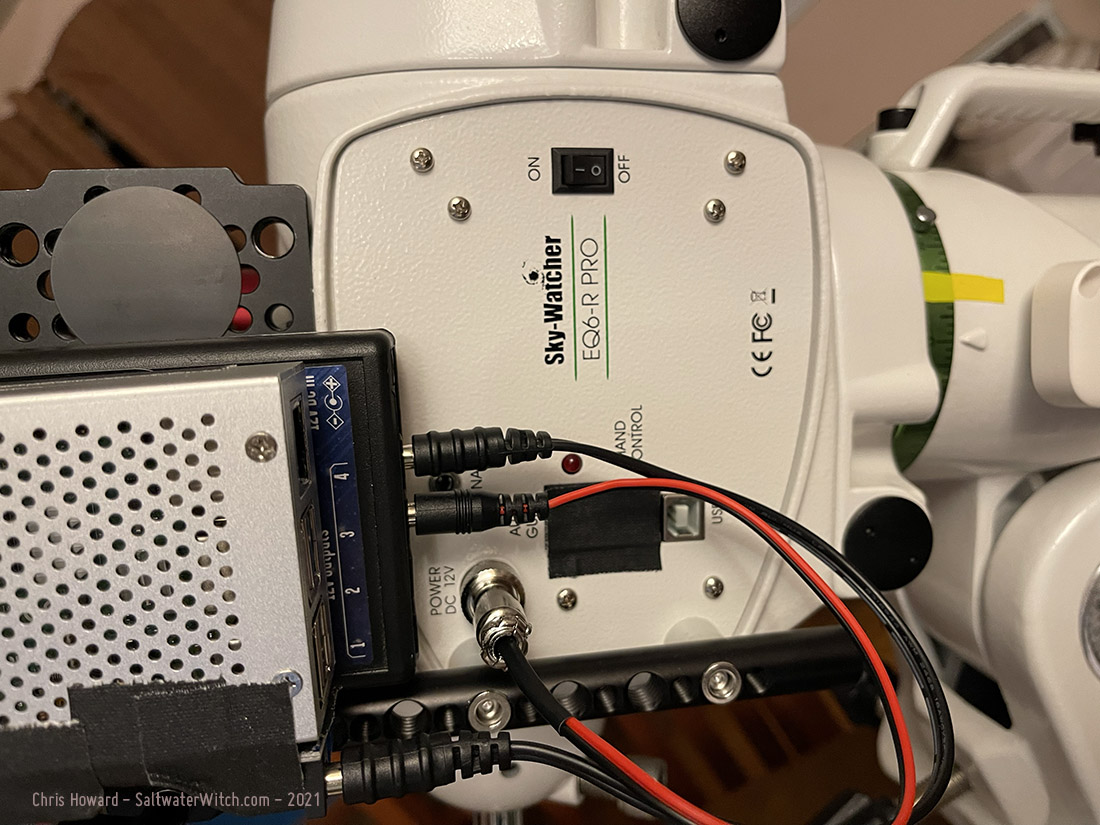

I made this to supply power to the mount from my Pegasus Pocket Powerbox, which I have on a 15mm rail and SmallRig aluminum cheese plate (https://www.amazon.com/dp/B019C2ZM8Q).

Here's the cable plugged into the Pegasus PPB, powering the Sky-Watcher mount. Tested and woks beautifully!

Posted September 13, 2021

Wide-field Narrowband Setup

Setting up and testing my wide-field astro gear: the William Optics SpaceCat 51 primary scope, 200mm guide scope, and everything else is ZWO--autofocuser (EAF), ASI120MM-S mono guide camera, ASI1600MM-Pro monochrome primary camera, and EFW with my Astronomik 6nm narrowband filters and the new Antlia 3 nanometer hydrogen-alpha filter. I switched to a guide scope from off-axis guiding with this setup because focusing with the different thicknesses of the filter material pushed my guide focus a bit too far. I was using this 50mm/200mm FL William Optics guide scope with the 800mm Newt because I had the same situation, narrowband filters mixed with near infrared filters with different brands and glass thickness.

Posted September 8, 2021

ZWO EFW Update

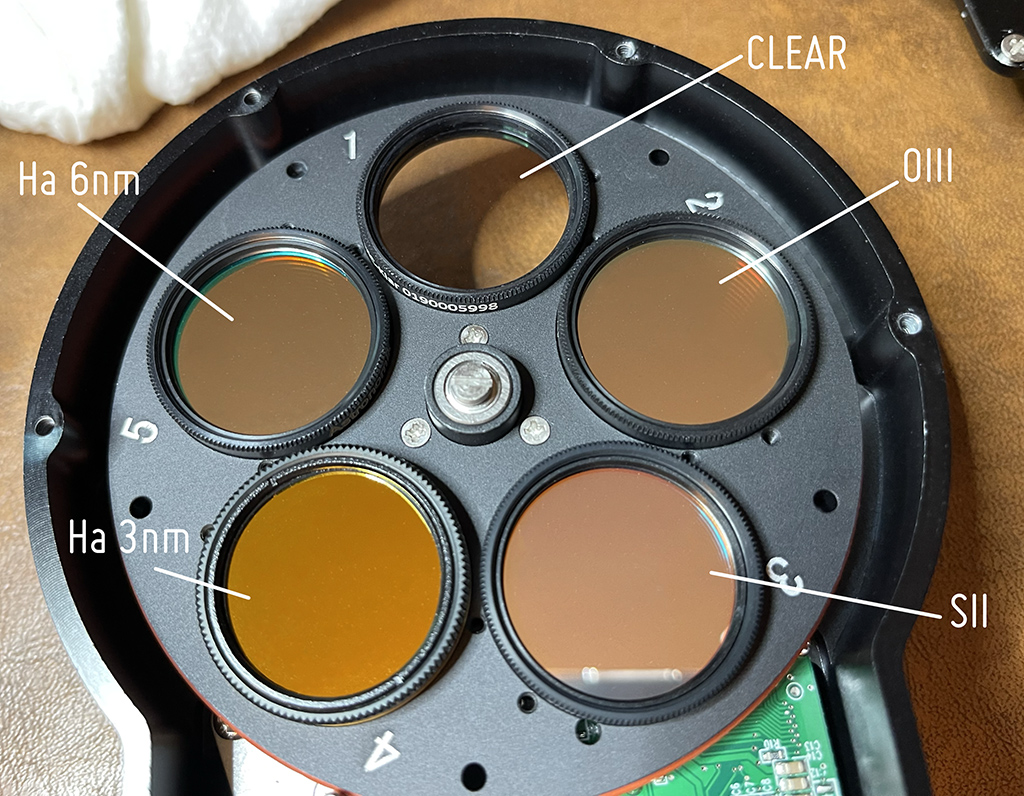

Added the Antlia 3nm Hydrogen-alpha filter in the ZWO filter wheel, and took a pic, added labels to make sure I remember where the filters are. Before this switch-up I had two near-infrared filters (a 680nm and 850nm) in slots 4 and 5, with my Astronomik 6 nanometer Ha filter in the first position. And just to make things as uncomplicated as possible I have the OIII (Oxygen 3) filter in position 2, and SII (Sulfur 2) in 3.

Posted September 4, 2021

Testing the Narrowband Rig with the New OTA

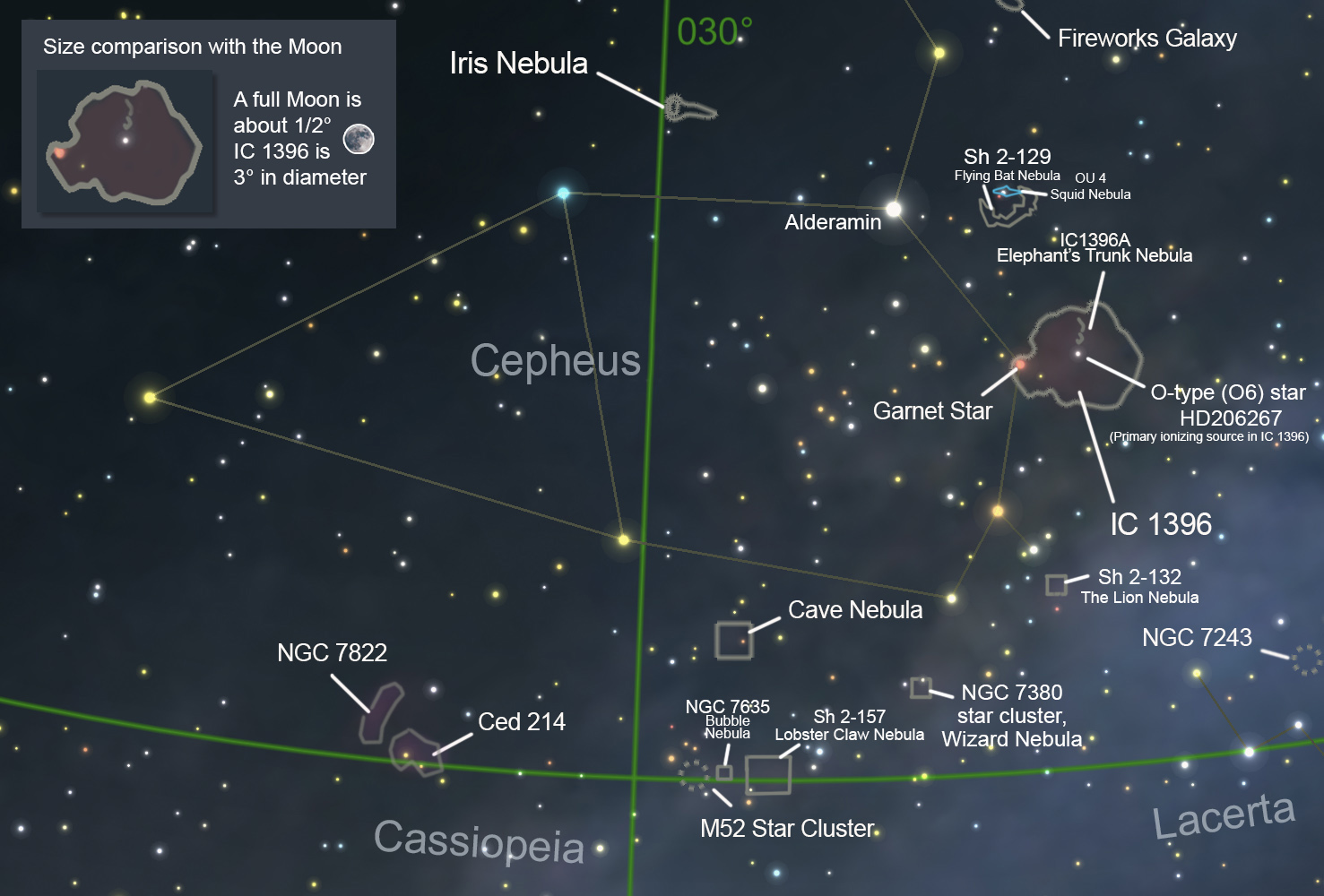

First narrowband test with the new Apertura Newtonian scope, although it was barely a test—31 sub-exposures in Ha before the clouds started rolling in, and with a very bright full moon in the sky. IC 1396 is a large (3 degrees in diameter) emission nebula and star-forming region in the constellation Cepheus, about 2400 lightyears away. Within IC 1396 is the Elephant's Trunk Nebula catalogued as IC 1396A, pictured here in hydrogen-alpha (narrowband). This structure is well over a hundred trillion miles long (roughly 20 lightyears), so if you want to get from the top to the bottom you'd better have a pretty fast vehicle.

Notes: 31 x 240 second subs in Ha. Apertura 8" Newtonian 880mm FL at f/4.4, ZWO ASI1600MM-Pro monochrome camera, Astronomik 6nm Hydrogen-alpha filter, SkyWatcher EQ6-R Pro mount, controller: INDI/Ekos/KStars. I managed to capture 31 subs of IC1396A, but no calibration frames—that's only half the subs I would normally want for this one in Hydrogen-alpha. I was not dithering here either, which is something I normally have on, and the result is some "walking noise" which is pattern noise in one direction--top-right to bottom left, in this case, introduced either by polar alignment drift or differential flexure between the guide scope and the OTA (this is the most likely suspect here, but not absolutely sure). Guiding total RMS averaged around 1 arcsecond the whole time, not the best, but I attributed it to the full moon, lack of contrast, but who knows. I didn't see any walking noise with the color rig, but even so, I'm going to go with off-axis guiding next time th eskies clear and see what happens!

Clouds swept in around midnight, and then it rained through the night, so I took what I could get and did some mild processing. There's serious coma around the edges. I have the stars pretty well dialed in with the color train, but not here. I have some measuring and caliper work to do!

The area around the constellation Cepheus is an astrophotography buffet, and because the constellation is circumpolar, it's in the night sky for at least half the year—if you're anywhere near the north. Both the Iris Nebula and the Fireworks Galaxy, two amazing deep sky objects I captured last week, are here, along with the Elephant's Trunk nebula, Cave and Wizard nebulas—and a lot more! Some of these targets span the border with Cassiopeia at the bottom.

BiColor version of the central region of the Elephant's Trunk Nebula--Hydrogen-alpha and Oxygen 3:

Posted June 25, 2021

Our moon

There's a beautiful moon out there tonight! Nikon D750, AstroTech AT6RC 1350mm f/9, 1/2500 sec exposure.

Posted June 23, 2021

What is deep sky astrophotography anyway?

What actually happens when we take a long exposure image of a deep sky object like a nebula?

The short answer is we capture light, like any other kind of photography. That's what the sensors in our cameras are designed to do. During long exposure imaging of a nearby nebula, my astro camera is detecting millions of photons, individual particles of light, released thousands of lightyears away when the intense radiation from a star ionized the surrounding interstellar medium, mostly clouds of hydrogen. You often see these referred to as HII (H2) regions, which are massive clouds of ionized hydrogen. Our cameras detect the individual particles of light emitted by hydrogen atoms—that's deep sky astrophotography right there, in one line. What's happening at a detail level is a hydrogen atom, bathed in intense UV radiation from a star, loses an electron and becomes positively charged, which isn't stable. It then releases a photon (light) when it gains an electron and returns to a neutral state. This is the ionization process—continuous energetic state changes across clouds of hydrogen that span trillions of cubic kilometers, and this process goes on for billions of years. It's all photons, particles of light without mass, continuously shooting off in all directions, generated when hydrogen atoms return to their stable state. And some tiny fraction of those photons arrive at our little planet, go through the atmosphere above New Hampshire, through the telescope I have focused on a point in the sky to hit one of the millions of photo sites on the camera sensor (my monochrome camera has a 16 megapixel sensor—11.7 million pixels). So, if I say I'm shooting a four-minute exposure, it means the "shutter" is open for 240 seconds, capturing photons the whole time, and the number of photons striking each site or "pixel" is converted into a value that, when read out, represents the light and dark values and gradients in an image.

Meanwhile the earth is rotating rapidly, a degree every four minutes, and if I want the stars to look like stars and not streaks of light, I need to mount the telescope on a device that moves precisely with the rotation of the earth. But that's a whole other paragraph for another blog post.

Posted June 22, 2021

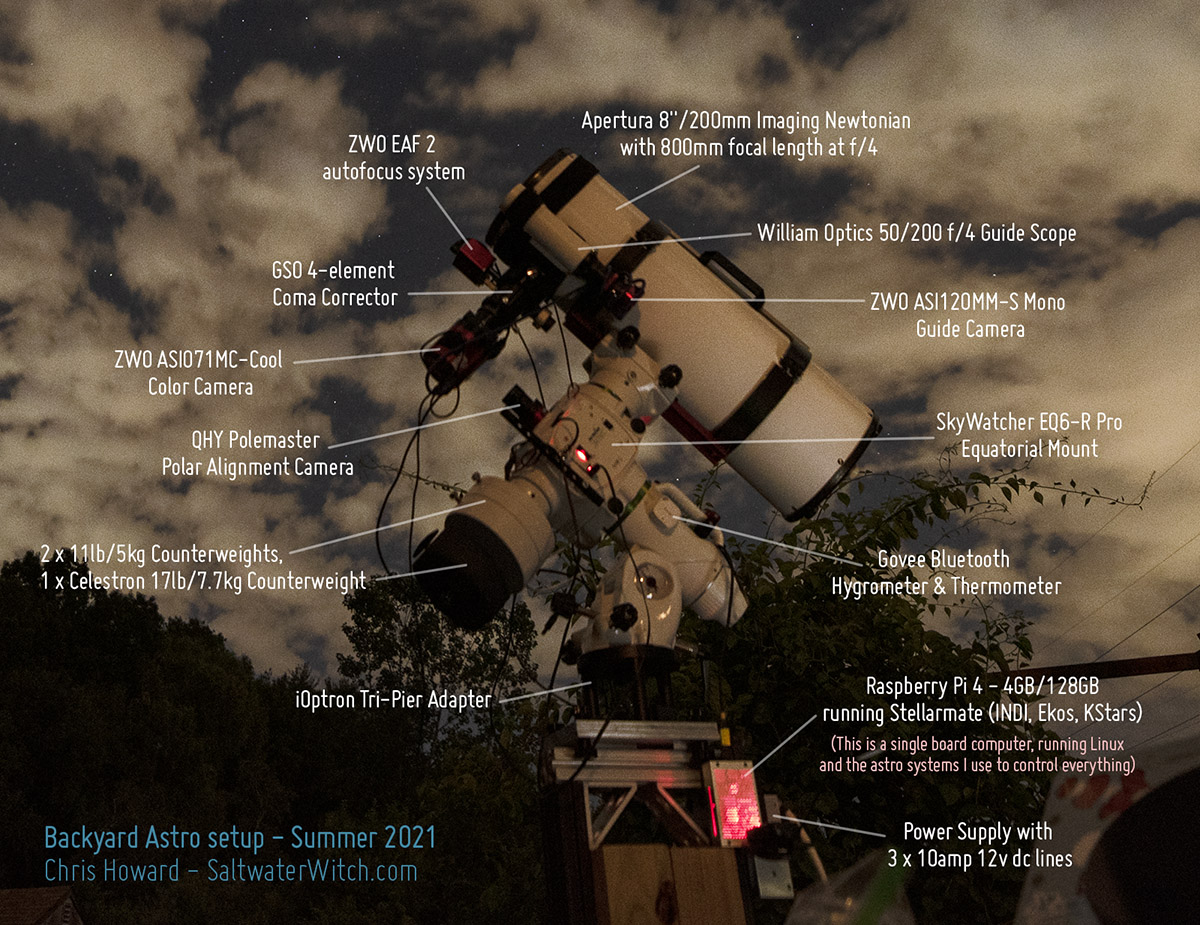

My Backyard Astro Setup - Summer 2021

This is the gear I currently have on the pier. I'm currently running with the color imaging train, and I will continue to until I get the coma correction dialed in. I'll try other cameras after that, including monochrome/narrowband.

Here's what things look like during the day. The micro-observatory project is on hold until I can buy a replacement for the CEM25P mount.

Posted June 19, 2021

Waiting for the skies to clear

I shot this a couple nights ago with the Nikon D750 and Irix 15mm lens, all set up for the Iris Nebula, but couldn't get started until after midnight with these clouds sweeping through. See my last post for the Iris Nebula image.