Back up, see if you can get M33 in...

I didn't have much time last night, so I just went with the Nikon D750 + 70-300mm lens on the iOptron SkyGuider Pro. And shot 20 exposures of M31. I was actually just wheeling the camera around the sky, adjusting focus at 70mm when I saw Andromeda Galaxy in the upper left, and there was M33 Triangulum in the lower corner. This is cropped from the full image, and I probably could have framed these better, but I didn't feel like pushing my luck. M33 was down by the bottom edge. So I went with this, 20 stacked frames in DSS:

And then a little later I shot 51 25 second shots of M45, the Pleiades--this time at 300mm:

Posted October 5, 2019

M31 Andromeda off the red end of the spectrum

The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) is our largest and most magnificent galactic neighbor, about 2.5 million light-years away from earth (or 780 kiloparsecs if you're of a more serious demeanor). Here's my bi-color version in near-IR and hydrogen-alpha. With a 685nm IR longpass filter I have managed to get a ring in M110 (NGC 205) the dwarf elliptical galaxy and satellite of Andromeda (center bottom). Wasn't expecting that. I am assuming the rings are an artifact of processing or cut-out gaps between bandpasses in the filtering because M110 is an elliptical galaxy, which are evenly distributed bundles of stars without arms or distinguishable belts like a spiral galaxy, e.g., M31, Milky Way.

Anyway, I'm enjoying the variation I'm getting with infrared imaging. More on the way! I may upgrade to the Astrodon Sloan Gen2 i’ (695 - 844nm) near IR filter at some point, but I'm happy so far with the results of the less expensive Optolong 685nm.

M31 in color, one my images from early this year:

Posted September 30, 2019

Sharpless 2-132

This is my second attempt with Sh2-132, sometimes called the "Lion Nebula" or "Lion's Mane", a roughly square-shaped emission nebula--or diamond in this rotation. Sharpless 2-132 is very faint and tough to capture without resorting to 10 or 20-minute exposures, which in turn requires outstanding alignment and guiding, not to mention a cooled camera and a good stretch of clear night sky. I ran at a steady -20C for 31 exposures. Sh2-132 is also in the middle (or behind) a dense field of stars, and that makes processing difficult when you're trying to bring out those faint cloudy structures. It's just too easy to bloat and overexpose the stars at the same time. All about balance with stretching and keeping an eye on your stars!

So far I have only captured hydrogen-alpha frames. Sh2-132 also has a strong band of oxygen, stretching from the bright lower corner to the top. Find Sharpless 2-132 in the Perseus arm of our galaxy, on the border between the constellations Cepheus and Lacerta.

Imaging notes: William Optics GT81 at f/4.7 with WO 0.8x Flat6A II, Astronomik Ha 6nm filter, Moonlite focuser, ZWO ASI120MM OAG, Imaging camera: ZWO ASI1600MM Pro cooled mono on an Orion Atlas EQ-G mount. Stacked in DSS, processed in PS CC 2019. 31 x 600 second exposures.

Posted September 30, 2019

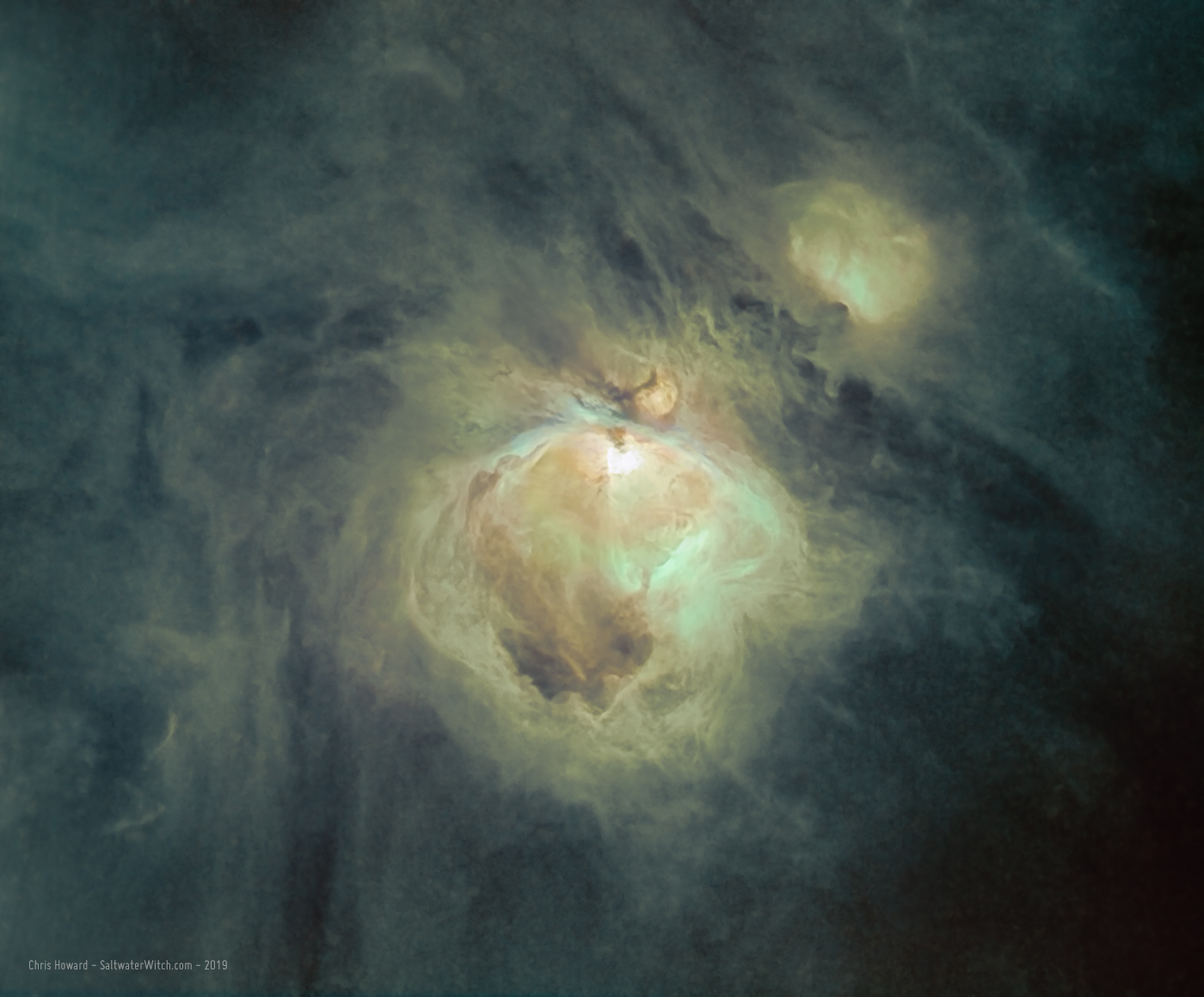

Orion Nebula (M42) in the SHO Hubble Palette

I have been thinking about how to represent false-color imaging for deep sky objects, and I've been keeping more of that abundant hydrogen green in the mix when doing SHO Hubble Palette images, where we map Sulfur, Hydrogen, and Oxygen bandpasses to Red Green Blue (RGB). Because hydrogen is--by a wide margin--the most abundant element in the universe, and many of these nebulae are HII Regions (vast expanses of interstellar ionized hydrogen), there ought to be more green in SHO images than we normally see. It's become standard to go heavy on a rust red and deep blue, with most of the green removed. All of these color choices are esthetic choices. The images I'm posting come from the data from three separate filters, Ha, OIII, and SII, so in a sense there are no incorrect color levels--within reason.

You do see a lot of color (LRGB) imaging with a target like M42, and with corresponding heavy reds and browns of bandpasses on the red end of the spectrum--and heading off into infrared. Most of my shots of Orion Nebula from past years has been in RGB with a luminance layer.

In the first set I toned the hydrogen green way down--actually all the colors are lower--until I'm just getting a nice green cast over everything.

I expanded on this in an Astrobin comment, dropping it here:

I'm going to reprocess data for some recent targets, see how they turn out. I think the reasoning is sound--that we should see more green with SHO, but we'll have to see how the images look. I know many handle this already by going with HSO to map Ha to Red, which makes a lot of sense, closer to where Ha is on the EM spectrum, even if we put sulfur in Green with this pattern. At the end of the day, though, it's still about how beautiful these images of nebulae look, and how each of us measures that beauty. It could also be that dozens of others have gone through this exact cycle with color levels and patterns and ended up back where we are today, simply because the stronger blues and reds are more appealing! I think one of the best things about this hobby/obsession is that it's data driven, and when I get new data and I try new techniques--and I like what I see, I can go back and reprocess data and try these techniques on other targets. There's something very powerful about this.

M42 Orion Nebula with the stars removed. I used the star removal in Annie's Astro Actions in Photoshop, which gets you 90% there, with some cleanup around the remnants of larger stars. Okay, this looks like H.R. Giger's version of the Orion Nebula.

To show you what I mean by "no incorrect color levels", this is the same imaging data, from the same stacked Ha, OIII, and SII frames. I just went in a different direction with which bandpass to stress--oxygen in this case, with stronger blues. It's strange how the "running man" shape in Sh2-279 Running Man Nebula, the brightish cloud above Orion, only appears faintly in narrowband. And in Orion, on the bottom right side, there's the weird chicken leg of hydrogen that now stands out behind the wispy pale clouds that ring the nebula.

And here's the same data set in HSO, with hydrogen-alpha mapped to red in RGB, sulfur green, and oxygen blue. You could argue that this is slightly more natural, as the hydrogen-alpha line is off the red end of the visible spectrum at 656nm, just this side of infrared. Mapping Ha to red makes sense, but mapping sulfur to green doesn't. The sulfur line is also on the red end of the spectrum, which is why normal RGB images of most deep sky objects taken with a DSLR or OSC camera are usually very red.

Imaging notes: William Optics GT81 at f/4.7 with WO 0.8x Flat6A II, Astronomik Ha, OIII, SII 6nm filters, Moonlite focuser, ZWO ASI120MM OAG, Imaging camera: ZWO ASI1600MM Pro cooled mono on an Orion Atlas EQ-G mount. Stacked in DSS, processed in PS CC 2019. 40 x 120 second exposures for each filter.

Posted September 29, 2019

Hanging out on the border between Cepheus and Cassiopeia

NGC 7822, Sharpless 171, Ced 214 region, along with the star cluster, Berkeley 59 at the top left. The bright core on the right is a massive star-forming complex that lights up most of the surrounding clouds of interstellar hydrogen and oxygen between Cepheus and Cassiopeia.

Imaging notes: William Optics GT81 at f/4.7 with WO 0.8x Flat6A II, Astronomik Ha, OIII filters, Moonlite focuser, ZWO ASI120MM OAG, Imaging camera: ZWO ASI1600MM Pro cooled mono on an Orion Atlas EQ-G mount. Stacked in DSS, processed in PS CC 2019. Bi-color Ha and OIII, 13 x 300 second exposures for each filter.

Posted September 28, 2019

Night sky--get out and see it once in a while

Sure, automating your astro systems is a wonderful thing--computers, programmable controllers, sensors tied to cameras, motorized telescope mounts, and other hardware were made for this. Bringing them all under a single application, or a set of applications and protocols, makes the process of scheduling imaging runs relatively easy--slewing to targets, focusing, plate solving, image capture sequences, auto-guiding--everything machines do very well. It's what they're good at. And yes, there's a lot of preparation, configuration, even tinkering involved in getting these systems to run smoothly through the night--and that goes for all of them. I don't know of an astronomical equipment or observatory control suite that just works out of the box. That doesn't exist yet.

Back to "Sure, automating your astro systems is a wonderful thing..." because you know there's going to be a "but", or in this case, a "just".

Just don't forget to get out there and look at the sky--if you can. If you're shooting narrowband targets in a red zone, maybe there isn't much to look at above you but the pale glow of street lights. Sorry to hear that, but it's awesome to see you're persevering anyway. I've seen some kick-ass narrowband DSO images on Astrobin shot from the middle of LA. Technology will find a way--or rather, people will reconfigure or refine the technology to find a way. That's what we're good at.

Anyway, I happen to be out in the backyard at 3 in the morning with my Nikon D750 and 24mm lens on a tripod. You know, like you do. I only took one shot--this one of the constellation Orion from a low angle with some of my equipment in the foreground. I spent the rest of the time just looking up, doing some honest to goodness stargazing. The universe really is awesome. I mean that in the true sense of the word, not the cool California sense, which it also is, of course.

If you don't have clear skies tonight, I hope you will be blessed with several in a row very soon!

Posted September 28, 2019

High-gain Test - Gathering Narrowband Data

Autumn is officially here, and this is the season of the Pleiades, Orion, the nebulae in the constellations of Perseus, Monoceros, Auriga, Taurus, and Gemini. Now, M42 isn't in view until 2am, so that had to be the last in the sequence. And, yes, you can tell I was just dorking around with filters with our galactic neighbor, Andromeda M31, in near IR and hydrogen-alpha. I know M31 is a decent Ha target, and you can see some wonderful images in Ha-RGB out there in the world, but I had never tried shooting 2-minute subs of M31 with a 685nm long pass filter.

I ran the ZWO ASI1600MM-Pro mono CMOS camera at a gain of 200 and offset of 65 in the following shots. And no calibration frames for any of these. Higher gain reduces dynamic range, but you're also reducing read noise and gaining (ha ha) resolution and the ability to shoot shorter exposures--and more of them, and if you take enough subs, this should balance things out. There are miles of discussion on gain and offset in astro-imaging, but I was recently reading Jon Rista's comments in an astrobin forum thread and that got me to test out higher gain/offset.

M31 in Near-IR + Ha

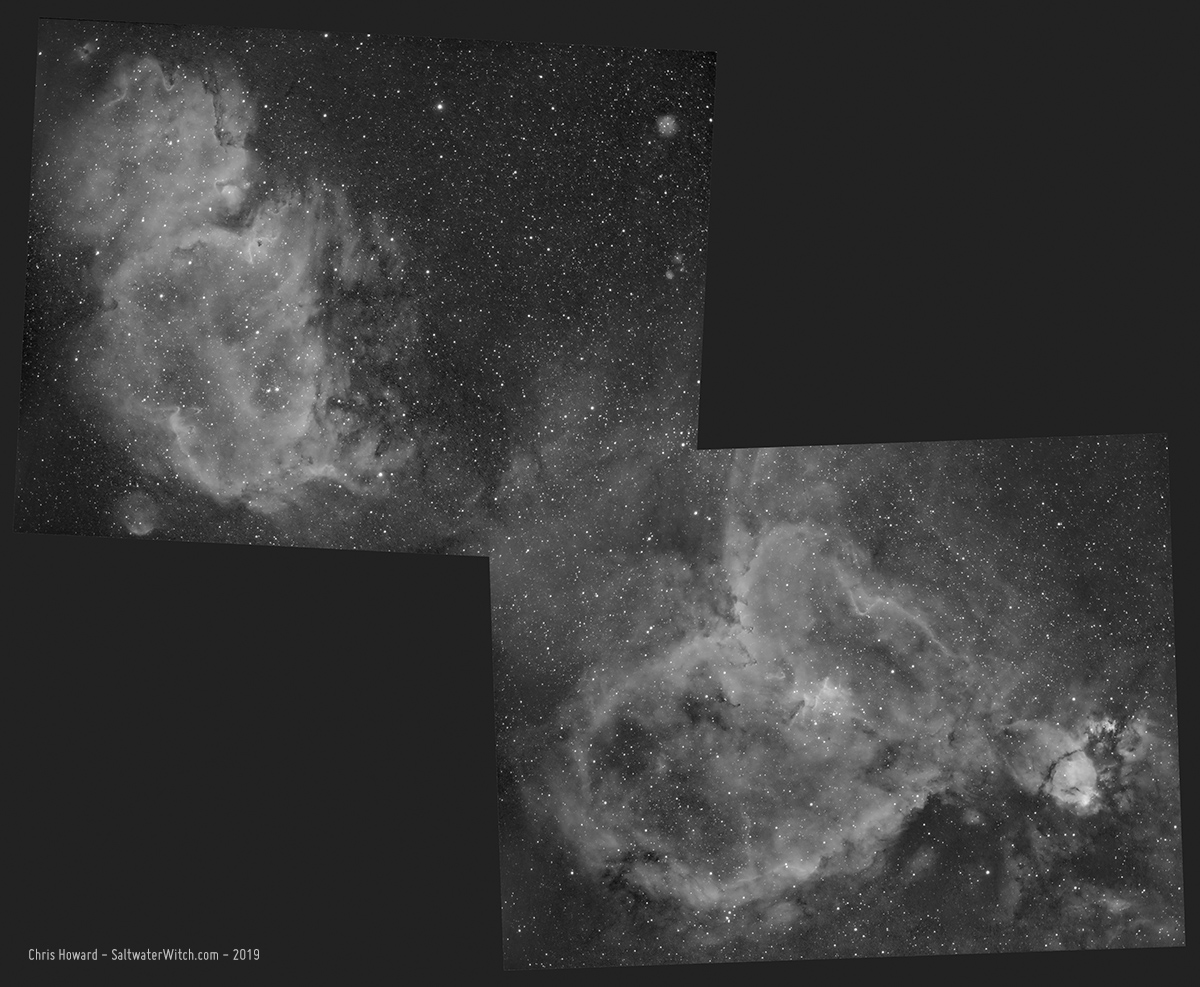

I moved over to Cassiopeia and shot 40 x 4-minute subs each of IC 1805 (Heart Nebula) and IC 1848 (Soul Nebula) in Hydrogen-alpha. Here's the stitched together pair:

Still waiting for Orion to get above 30°, I spent some time on NGC 1499 "California Nebula"

And Orion is back in the sky! Sure, you have to get up at 3 in the freakin' morning to see it with your own eyes. Or you can program your astro imaging system to stay up all night and take pictures without you. Here's M42, Orion Nebula, along with M43, De Mairan's Nebula--that's the spherical-looking cloud formation with the big bite taken out of it. And above that, shining brightly, Sh2-279 Running Man Nebula--although the famous running man shape isn't clear in hydrogen alpha. I'm not sure how well it comes out with oxygen III and sulfur II, but I'll come back another night to capture the OIII and SII frames. Notes: 31 x 240 second exposures in Ha + 20x 10 second subs just for the Trapezium (the super bright core of the Orion Nebula--so bright I have to take separate short exposure shots and merge it back in processing). William Optics GT81 APO refractor, ZWO ASI1600MM-Pro mono camera, Astronomik 6nm Ha filter.

Posted September 26, 2019

Very wide-angle view of the sky

Here's my first night out with the Irix 15mm f/2.4 Blackstone (the heavier, more durable, aluminum and magnesium alloy housing version of this lens). And I'm impressed with just a few shots, wide-open aperture, and single 15 - 20 second exposures--no tripod, although I rested the Nikon on the deck railing.